Your ideal learning environment #

Talks about learning technology often center on technology. Instead, I want to begin by asking: what do you want learning to be like—for yourself? If you could snap your fingers and drop yourself into a perfect learning environment, what’s your ideal?

One way to start thinking about this question is to ask: what were the most rewarding high-growth periods of your life?

I’ve noticed two patterns in answers to this question: first, people will tell me about a time when they learned a lot, but learning wasn’t the point. Instead, they were immersed in a situation with real personal meaning—like a startup, a research project, an artistic urge, or just a fiery curiosity. They dove in, got their hands dirty, and learned whatever was important along the way. And secondly: in these stories, learning really worked. People emerged feeling transformed, newly capable, filled with insight and understanding that has stayed with them years later.

These stories are so vivid because learning isn’t usually like this. People are often telling me somewhat wistfully about experiences that happened years or decades earlier. Learning rarely feels so subordinated to an authentic pursuit. Often if we try to “just dive in”, we hit a brick wall, or find ourselves uneasily cargo culting others, with no real understanding.

Why can’t we “just dive in” all the time?

Instead it often feels like we have to put our aims on hold while we go do some homework—learn properly. Worse, learning so often just doesn’t really work! We take the class, we read the book… but when we try to put that knowledge into practice, it’s fragile; it doesn’t transfer well. Then we’ll often find that we’ve forgotten half of it by the time we try to use it.

Why does learning so often fail to actually work?

These questions connect to an age-old conflict among educators and learning scientists—between implicit learning (also called discovery learning, inquiry learning, or situated learning), and guided learning (often represented by cognitive psychologists). Advocates of implicit learning methods argue that we should prioritize discovery, motivation, authentic involvement, and being situated in a community of practice. In the opposing camp, cognitive psychologists argue that you really do need to pay attention to architecture of cognition, long-term memory, procedural fluency, and to scaffold appropriately for cognitive load.

In my view, each of these points of view contains a lot of truth. And they each wrongly deny the other’s position, to their mutual detriment. Implicit learning aptly recognizes meaning and emotion, but ignores the often decisive constraints of cognition—what we usually need to make “learning actually work”. Guided learning advocates are focused on making learning work, and they sometimes succeed, but usually by sacrificing the purposeful sense of immersion we love about those rewarding high-growth periods.

One obvious approach is to try to compromise. Project-based learning is a good representation of that. By creating a scaffolded sequence of projects, the suggestion is that we can get some of the benefits of implicit learning—authenticity, motivation, transfer—while also exerting some of the instructional control and cognitive awareness typical of traditional courses. But so often it ends up getting the worst of both worlds—neither motivation and meaning, nor adequate guidance, explanation, and cognitive support.

In university, I was interested in 3D game programming, so I took a project-based course on computer graphics. The trouble was that those projects weren’t my projects. So a few weeks in, I found myself implementing a ray marching shader for more efficient bump mapping. Worse, because this course was trying to take project-based learning seriously, there weren't long textbook readings or problem sets. I found myself just translating math I’d been given into code. What I ended up with was a project I didn't care about, implementing math I didn't understand.

Instead, I suggest: we should take both views seriously, and find a way to synthesize the two. You really do want to make doing-the-thing the primary activity. But the realities of cognitive psychology mean that in many cases, you really do need explicit guidance, scaffolding, practice, and attention to memory support.

Learning by immersion works naturalistically when the material has a low enough complexity relative to your prior knowledge that you can successfully process it on the fly, and when natural participation routinely reinforces everything important, so that you build fluency. When those conditions aren’t satisfied—which is most of the time—you’ll need some support.

You want to just dive in, and you want learning to actually work. To make that happen, we need to infuse your authentic projects with guided support, where necessary, inspired by the best ideas from cognitive psychology. And if there’s something that requires more focused, explicit learning experiences, you want those experiences to be utterly in service to your actual aims.

I’ve been thinking about this synthesis for many years, and honestly: I’ve mostly been pretty stuck! Recently, though, I’ve been thinking a lot about AI. I know: eye-roll! Pretty much every mention of AI in learning technologies gets an eye-roll from me. But I confess: the possibility of AI has helped me finally get what feels like some traction on this problem. I’d like to share some of those early concepts today.

Demo, part 1: Tractable immersion #

We’ll explore this possible synthesis through a story in six parts.

Meet Sam. Sam studied computer science in university, and they’re now working as a software engineer at a big tech company. But Sam’s somewhat bored at their day job. Not everything is boring, though: every time Sam sees a tweet announcing a new result in brain-computer interfaces, they’re absolutely captivated. These projects seem so much more interesting. Sam pull up the papers, looking for some way to contribute, but they hit a brick wall—so many unfamiliar topics, all at once.

What if Sam could ask for help finding some meaningful way to start participating? With Sam’s permission, our AI—and let’s assume it’s a local AI—can build up a huge amount of context about their background. From old documents on Sam’s hard drive, our AI knows all about their university coursework. It can see their current skills through work projects. It knows something about Sam’s interests through their browsing history.

Sam’s excited about the idea of reproducing the paper’s data analysis. It seems to play to their strengths. They notice that the authors used a custom Python package to do their analysis, but that code was never published. That seems intriguing: Sam’s built open-source tools before. Maybe they could contribute here by building an open source version of this signal processing pipeline.

Demo, part 2: Guidance in action #

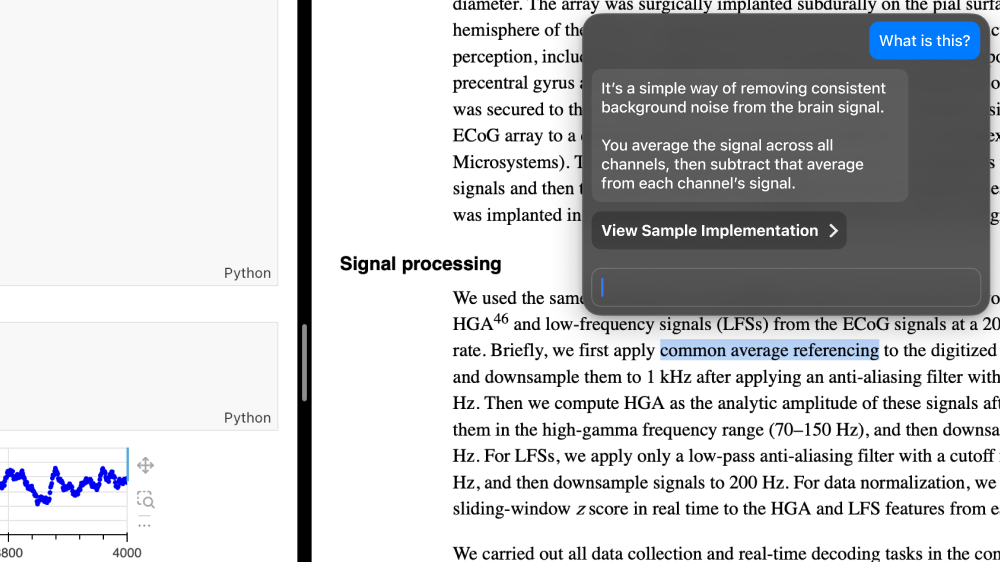

So—Sam dives in. They’ve found an open-access dataset, and they’ve taken the first steps to start working with it. Tools like Copilot help Sam get started, but to follow some of these signal processing steps, what Sam really needs here is something like Copilot, but with awareness of the paper in addition to the code, and with context about what Sam’s trying to do.

This AI system isn’t trapped in its own chatbox, or in the sidebar of one application. It can see what’s going on across multiple applications, and it can propose actions across multiple applications. Sam can click that button to view a changeset with the potential implementation. Then they can continue the conversation, smoothly switching into the context of the code editor.

Like, what’s this “axis=1” parameter? The explanation depends on context from the code editor, the paper being implemented, and also documentation that came with the dataset Sam’s working with. The AI underlines assumptions made based on specific information, turning them into links.

Here Sam clicks on that “In this dataset” link, and our AI opens the README to the relevant line.

All this is to support our central aim—that Sam can immerse themselves, as much as possible, in what they’re actually trying to do, but get the support they need to understand what they’re doing.

Demo, part 3: Synthesized dynamic media #

That support doesn’t have to just mean text.

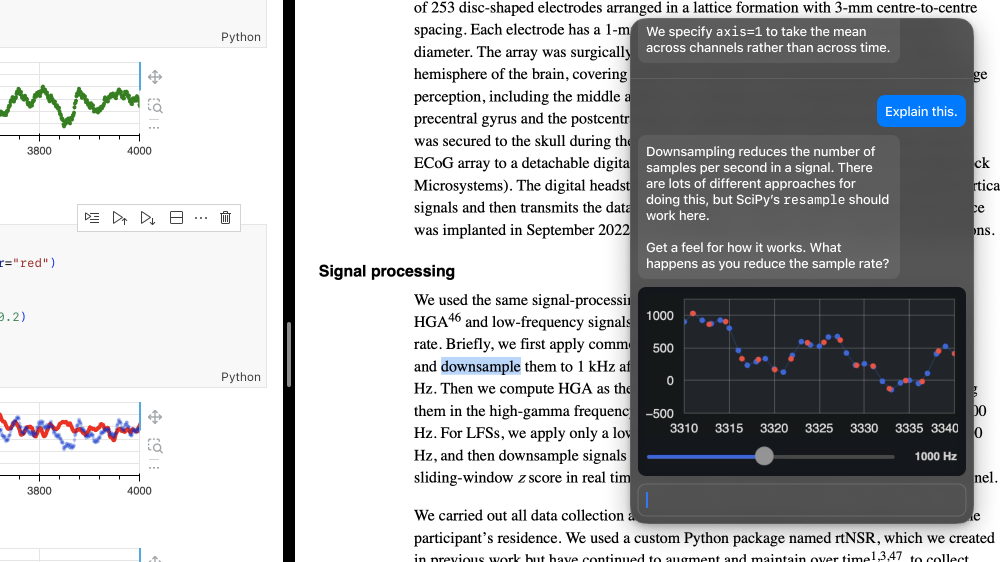

Sam next needs to implement a downsampling stage. This time, guidance includes synthesized dynamic media, so that Sam can understand what downsampling does through scaffolded immersion.

Sam doesn’t need to read an abstract explanation and try to imagine what that would do to different signals: instead, as they try different sampling rates, realtime feedback can help them internalize the effect on different signals. By playing with the dynamic media, Sam notices that some of the peaks are lost when the signal is downsampled.

These dynamic media aren’t trapped in the chatbox. They’re using the same input data and libraries Sam’s using in their notebook. At any time, Sam can just “view source” to tinker with this figure, or to use some of its code in their own notebook.

Demo, part 4: Contextualized study #

Now Sam presses on but as they dig into band-pass filters, the high-level explanations they can get from these short chat interactions really just don’t feel like enough. What’s a frequency domain? What’s a Nyquist rate? Sam can copy and paste some AI-generated code, but they don’t understand what’s going on at all. A chat interface is just not a great medium for long-from conceptual explanation. It’s time for something deeper.

The AI knows Sam’s background and aims here, so it suggests an undergraduate text with a practical focus. More importantly, the AI reassures Sam that they don’t necessarily need to read this entire thousand-page book right now. It focuses on Sam’s goal here and suggests a range of accessible paths that Sam can choose according to how deeply they’d like to understand these filters. It's made a personal map in the book’s table of contents.

So that, for instance, if Sam just wants to understand what these filters are doing and why, there's a 25-page path for that. But if they want to know the mathematical background—how these filters work—there's a deeper path. And if they want to be able to implement these filters themselves, there's an even deeper path. Sam can choose their journey here.

When Sam digs into the book, they'll find notes from the AI at the start of each section, and scattered throughout, which ground the material in Sam’s context, Sam’s project, Sam’s purpose. “This section will help you understand how to think of signals in terms of frequency spectra. That’s what low-pass filters manipulate.” Sam’s spending some time away from their project, in a more traditionally instructional setting, but that doesn’t mean the experience has to lose its connection to their authentic practice.

Incidentally, I’ve heard some technologists suggest that we should use AI to synthesize the whole book, bespoke for each person. But I think there’s a huge amount of value in shared canonical artifacts—in any given field, there are key texts that everyone can refer to, and they form common ground for the culture. I think we can preserve those by layering personalized context as a lens on top of texts like this.

In my ideal future, of course, our canonical shared artifacts are dynamic media, not digital representations of dead trees. But until all of our canonical works are rewritten, as a transitional measure, we can at least wave our hands and imagine that our AI could synthesize dynamic media versions of figures like this one.

Now, as Sam reads through the book, they can continue to engage with the text by asking questions, and our AI’s responses will continue to be grounded in their project.

As Sam highlights the text or makes comments about details which seem particularly important or surprising, those annotations won’t end up trapped in this PDF: they’ll feed into future discussion and practice, as we’ll see later.

In addition to Sam asking questions of the AI, the AI can insert questions for Sam to consider—again, grounded in their project—to promote deeper processing of the material.

And just as our AI guided Sam to the right sections of this thousand page book, it could point out which exercises might be most valuable, considering both Sam’s background and their aims. And it can connect the exercises to Sam’s aims so that, aspirationally, doing those problems feels continuous with Sam’s authentic practice. Even if the exercises do still feel somewhat decontextualized, Sam can at least feel more confident that the work is going to help them do what they want to do.

Interlude: Practice and memory #

Sam ends the day with some rewarding progress on their project, and a newfound understanding of quite a few topics. But this isn’t yet robust knowledge. Sam has very little fluency—if they try to use this material seriously, they’ll probably feel like they’re standing on shaky ground. And more prosaically, they’re likely to forget much of what they just learned.

I’d like to focus on memory for a moment. It’s worth asking: why do we sometimes remember conceptual material, and sometimes not? Often we take a class, or read a book, or even just look something up, and find that a short time later, we’ve retained almost nothing. But sometimes things seem to stick. Why is that?

There are some easier cases. If you’re learning something new in a domain you know well, each new fact connects to lots of prior knowledge. That creates more cues for recall and more opportunities for reinforcement. And if you’re in some setting where you need that knowledge every single day, you’ll find that your memory becomes reliable pretty quickly.

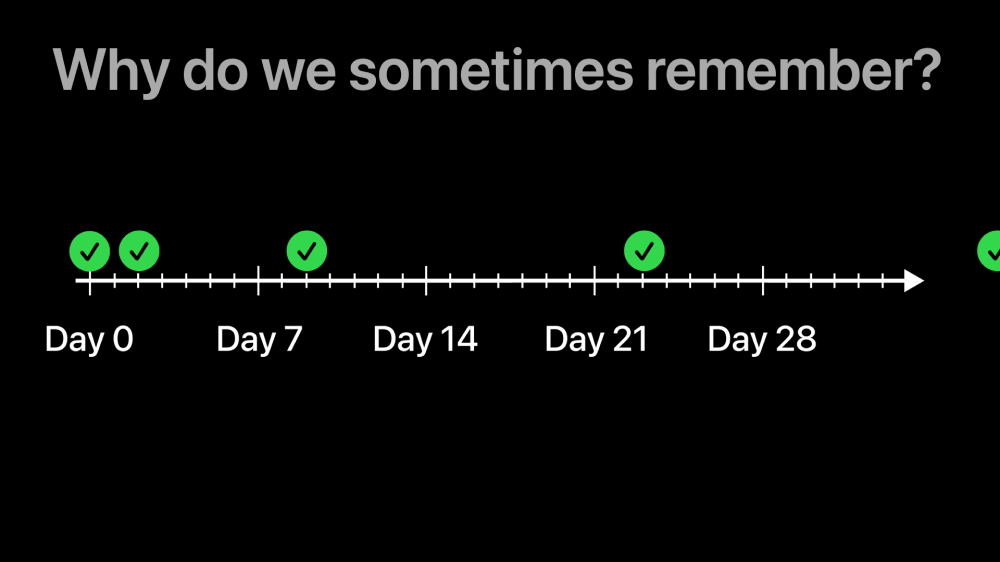

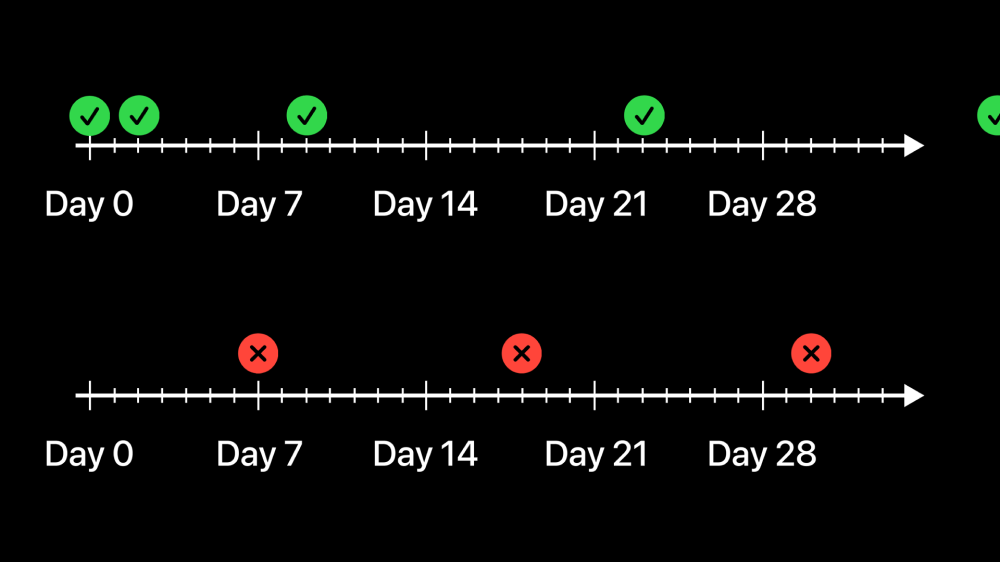

Conceptual material like what Sam’s learning doesn’t usually get reinforced every day like that. But sometimes the world conspires to give those memories the reinforcement they need. Sometimes you read about a topic, then later that evening, that topic comes up in conversation with a collaborator. You have to retrieve what you learned, and that retrieval reinforces the memory. Then, maybe, two days later you need to recall that knowledge again for a project. Each time you reinforce the memory this way, you forget it more slowly. Now perhaps a week can go by, and you’re still likely to remember. Then maybe a few weeks, and a few months, and so on. With a surprisingly small number of retrievals, if they’re placed close enough to each other to avoid forgetting, you can retain that knowledge for months or years.

By contrast, sometimes when you learn something, it doesn’t come up again until the next week. Then you try to retrieve that knowledge, but maybe it’s already been forgotten. So you have to look it up. That doesn’t reinforce your memory very much. And then if it doesn’t come up again for a while longer, you may still not remember next time. So you have to look it up yet again. And so on. The key insight here is that it’s possible to arrange the top timeline for yourself.

Courses sometimes do, when each problem set consistently interleaves knowledge from all the previous ones. But immersive learning—and for that matter most learning—usually doesn’t arrange this properly, so you usually forget a lot. What if this kind of reinforcement were woven into the grain of the learning medium?

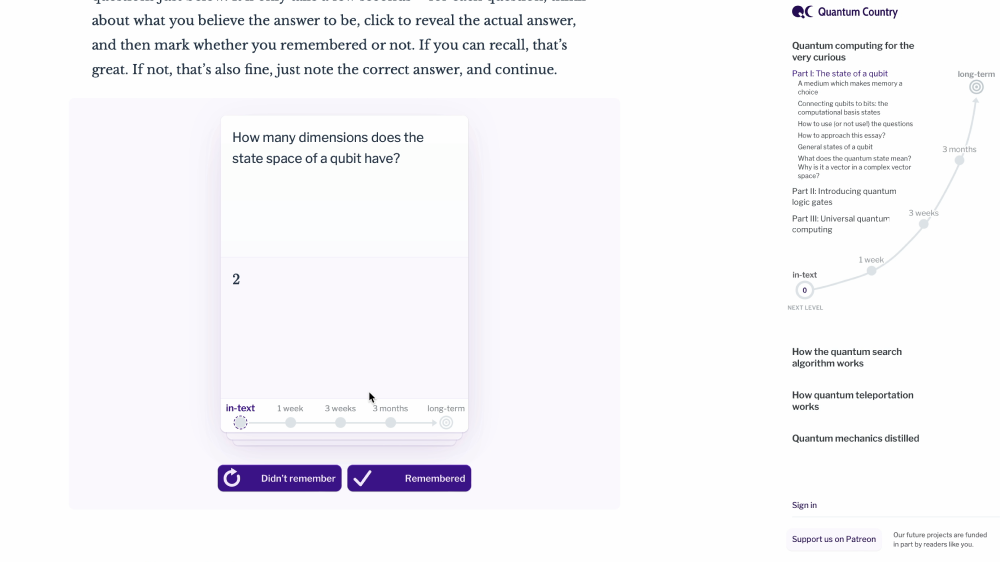

My collaborator Michael Nielsen and I created a quantum computing primer, Quantum Country, to explore this idea. It’s available for free online. If you head to quantum.country, you’ll see what looks at first like a normal book.

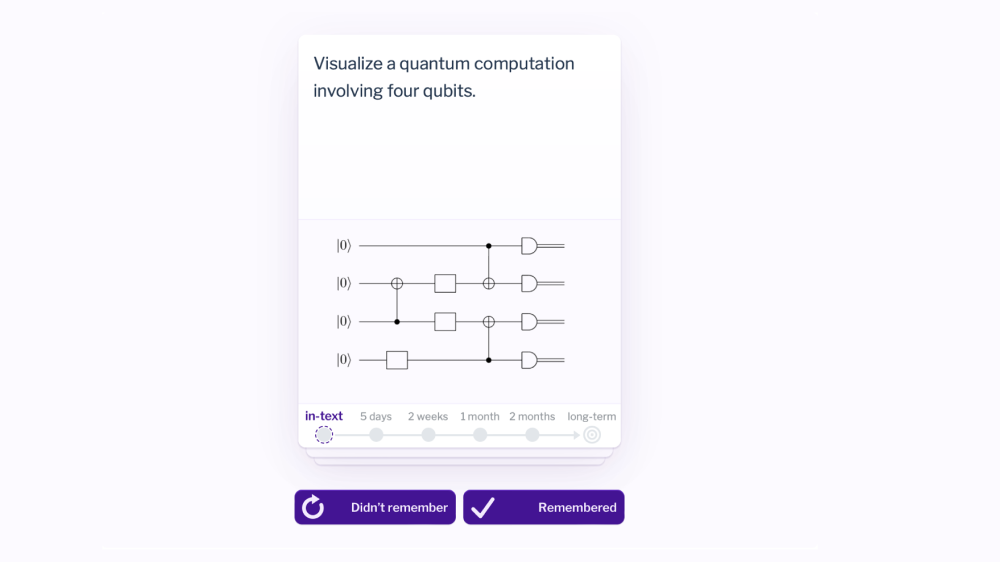

After a few minutes of reading, the text is interrupted with a small set of review questions. They’re designed to take just a few seconds each: think the answer to yourself, then mark whether or not you were able to answer correctly. So far, these look like simple flashcards. But as we’ve discussed, even if you can answer these questions now, that doesn’t mean you’ll be able to in a few weeks, or even in a few days.

Notice these markings along the bottom of each question. These represent intervals. So you practice the questions while you’re reading the text, then, one week later, you’ll get an email that says: “Hey, you’ve probably started to forget some of what you read. Do you want to take five minutes to quickly review that material again?” Each time you answer successfully, the interval increases—to a few weeks, then a few months, and so on. If you begin to forget, then the intervals tighten up to provide more reinforcement.

You may have seen systems like this before. Language learners and medical students often use tools called spaced repetition memory systems to remember vocabulary and basic facts. But the same cognitive mechanisms should work for more complex conceptual knowledge as well. There are 112 of these questions scattered through the first chapter of the book on that basis.

Quantum Country is a new medium—a mnemonic medium—integrating a spaced repetition memory system with an explanatory text to make it easier for people to absorb complex material reliably.

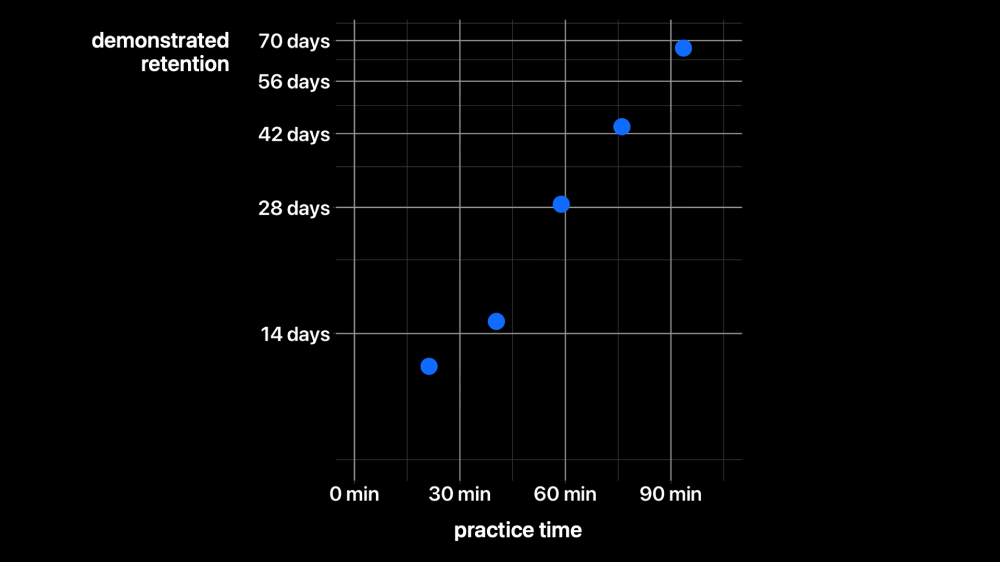

We now have millions of practice data points, so we can start to see how well it’s working. This plot shows the amount of time spent practicing, on the x axis, versus a reader’s demonstrated retention on the y axis— that is, how long a reader was able to go without practicing, and still answer at least 90% of questions correctly. These five dots represent the median user’s first five repetitions, for the first chapter. Notice that the y axis is logarithmic, so we’re seeing a nice exponential growth here. Each extra repetition—constant extra input—yields increasing output—i.e. retention.

In exchange for about an hour and a half of total practice, the median reader was able to correctly answer over a hundred detailed questions about the first chapter, after more than two months without practice. Now, the first chapter takes most readers about four hours to read the first time, so this plot implies that an extra overhead of less than 50% in time commitment can yield months or years of detailed retention.

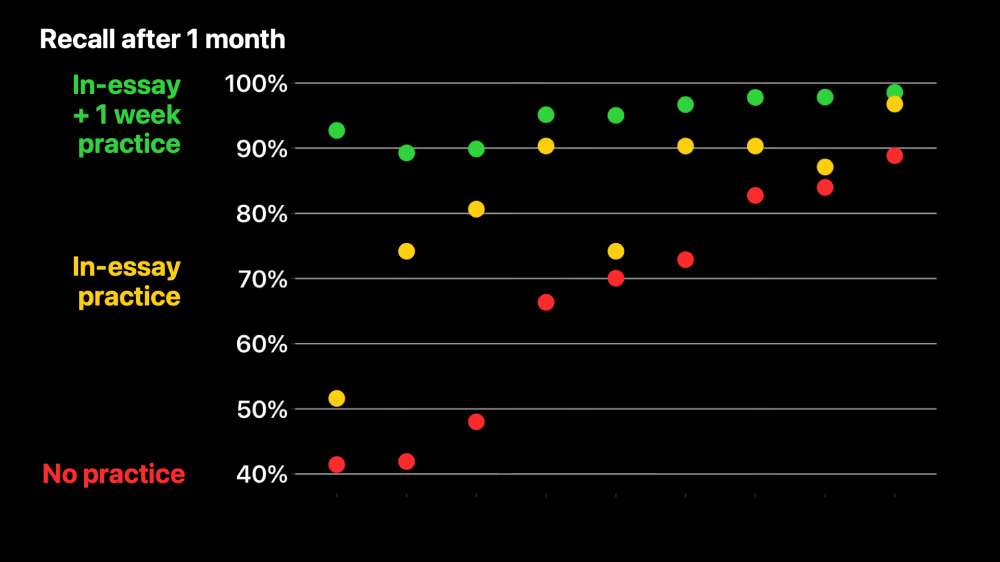

It’s also interesting to explore the counterfactual: how much would people forget without the extra reinforcement? As an experiment, we removed nine questions from the first chapter for some readers, then covertly reinserted the questions into those readers’ practice sessions a month later. This graph shows what happened.

These nine points represent those nine questions. The y axis shows the percentage of readers who were able to answer that question correctly after one month, with no support at all. You can see that some questions are harder than others. One month later, the majority of readers missed the hardest three questions, on the left, about 30% missed the middle three, and about 15% missed the easiest three.

Another group of users got practice while reading the essay, like we saw in the video a moment ago—and for any questions they missed, a bonus round of practice the next day. Then these questions disappeared for a month, at which point they were tested. These readers perform noticeably better, though a big chunk of them are still missing some of these questions.

Here’s one last group, like the previous one, except they got one extra round of practice a week after reading the book. Then we tested them again at the one month mark, and that’s what you’re seeing here. Each question takes six seconds on average to answer, so this is less than a minute of extra practice in total for these nine questions. But now for all of these questions, at least 90% of readers were able to answer correctly.

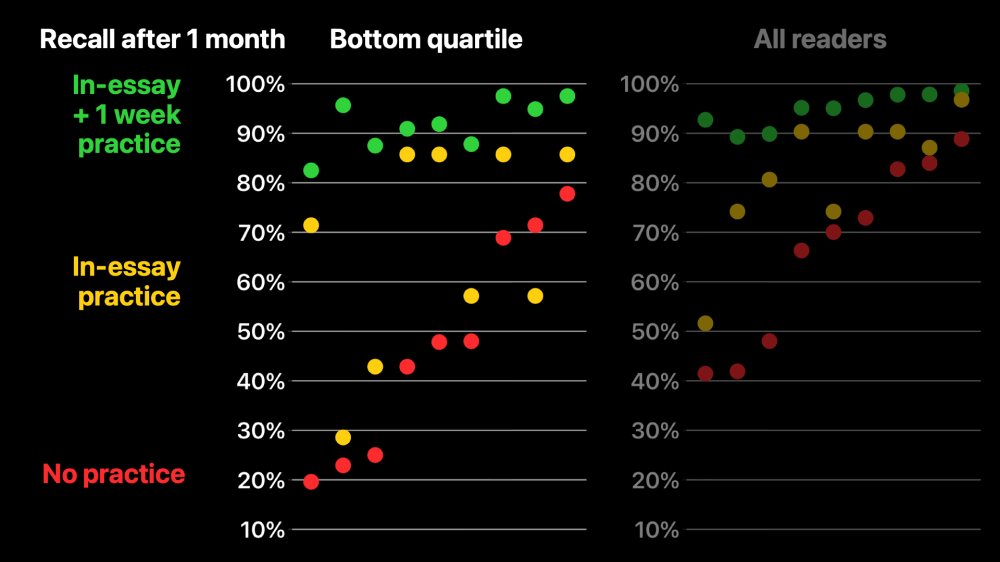

Of course, some readers have a much easier time than others. This left plot focuses on the bottom quartile of users—the readers who missed the most questions while they were first reading the essay. Notice I’ve had to lengthen the y axis downwards. We can see that without any practice, most of them forgot two thirds of these held-out questions. In-essay practice alone still left roughly half of them forgetting roughly half of the questions. But with one extra round of practice, even this bottom quartile of readers performs quite well.

Systems like Quantum Country are useful for more than just quantum computing. In my personal practice, I’ve accumulated thousands and thousands of questions. I write questions about scientific papers, about conversations, about lectures, about memorable meals. All this makes my daily life more rewarding, because I know that if I invest my attention in something, I will internalize it indefinitely.

Central to this is the idea of a daily ritual, a vessel for practice. Like meditation and exercise, I spend about ten minutes a day using my memory system. Because these exponential schedules are very efficient, those ten minutes are enough to maintain my memory for thousands of questions, and to allow me to add up to about forty new questions each day.

But I want to mention a few problems with these memory systems.

One is pattern matching: once a question comes up a few times, I may recognize the text of the question without really thinking about it. This creates the unpleasant feeling of parroting, but I suspect it often leaves my memory brittle: I’ll remember the answer, but only when cued exactly as I’ve practiced. I wish the questions had more variability.

Likewise, the questions are necessarily somewhat abstract. When I face a real problem in that domain, I won’t always recognize what knowledge I should use, or how to adapt it to the situation. A cognitive scientist would say I need to acquire schemas.

Unless I intervene, questions stay the same over years. They’re maintaining memory—but ideally, they would push for further processing—more depth over time.

Finally, returning to this talk’s thesis: memory systems are often too disconnected from my authentic practice. Say I’m studying a topic in signal processing for a creative project. Unless I’m careful, those questions probably won’t feel very connected to my project—they’ll feel like generic textbook questions about signal processing.

Demo, part 5: Dynamic practice #

Let’s return to Sam now, and see if we can apply some of these ideas about practice and memory. Sam did the work to study that signal processing material, so they want to make sure it actually sticks.

They install a home screen widget, which ambiently exposes them to practice prompts drawn from highlights, questions asked, and other activity the AI can access. Sam can flip through these questions while waiting in line or on the bus. Notice that this isn’t a generic signal processing question: it’s grounded in the details of Sam’s BCI project, so that, aspirationally, practice feels more continuous with authentic doing.

These synthesized prompts can vary each time they’re asked, so that Sam gets practice accessing the same idea from different angles. The prompts get deeper and more complex over time, as Sam gets more confident with the material. Notice also that this question isn’t so abstract: it’s really about applying what Sam’s learned, in a bite-sized form factor.

The widget can also include open-ended discussion questions. Here Sam gets elaborative feedback—an extra detail to consider in their answer.

When questions are synthesized like this, it’s important that Sam can steer them with feedback. Future questions will be synthesized accordingly.

So far, we’ve been looking at bite-sized questions Sam can answer while they’re out and about, but if they make time for a longer dedicated session, we can suggest meatier tasks, like this one. What’s more, we can move that work out of fake-practice-land and into Sam’s real context—the Jupyter notebook. Notice that the task is still framed in terms of Sam’s specific aims, rather than some generic signal processing problem.

Demo, part 6: Social connection #

Now, Sam got into this project not as a “learning exercise”, but as a way to start legitimately participating. To start working with BCIs while playing to existing strengths.

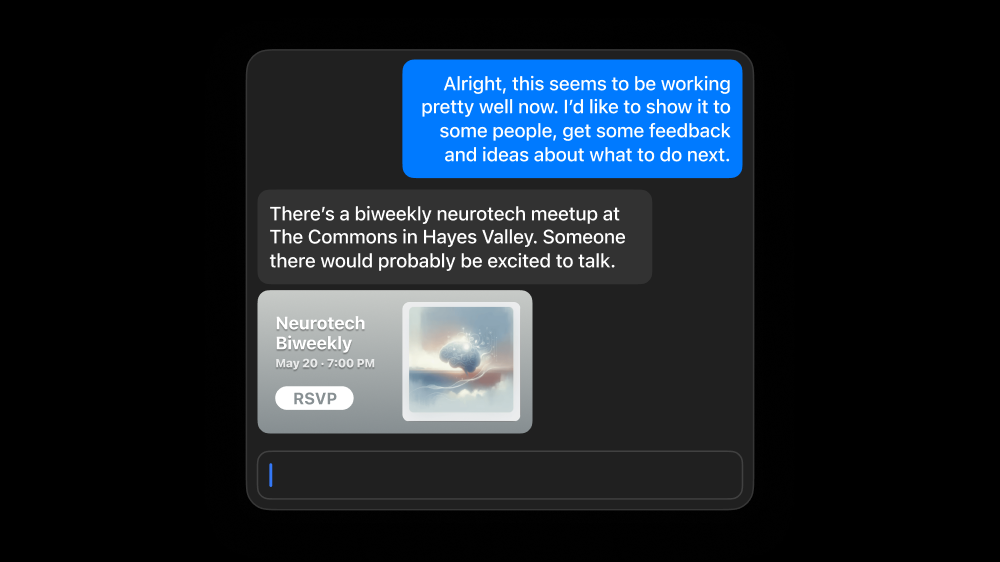

Just as our AI can help Sam find a tractable way into this space, it can also facilitate connections to communities of practice—here suggesting a local neurotech meetup. So Sam goes to the neurotech event, meets a local scientist, and sets up a coffee date. With permission, Sam records the meeting, knowing the notes will probably be helpful later.

And of course, Sam ends up surprised and intrigued quite a lot during this conversation. Our AI can notice these moments and help Sam metabolize them. Here that insight turns into a reflective practice prompt.

Design principles #

Four big design principles are threaded through Sam’s story. I’d like to review them now, and for each, point out the ways I think AI can help.

First, we bring guided learning to authentic contexts, rather than thinking of it as a separate activity. We’re able to make that happen by imagining an AI which can perceive and act across applications on Sam’s computer. And as the audio transcript at the end demonstrated, that can extend to activities outside the computer too. This AI can give appropriate guidance in part because—with permission and executing locally—it can learn from every piece of text that’s ever crossed Sam’s screen, every action they’ve taken on the computer. It can synthesize scaffolded dynamic media, so that Sam can learn by doing, but with guidance.

Then, when explicit learning activities are necessary, we suffuse them with authentic context. The AI grounds all the reading and practice Sam’s doing in their actual aims. It helps Sam match the learning activities to their depth of interest. It draws on important moments that happen when Sam is doing, like insights from that coffee meeting at the end, or questions asked while implementing parts of the project, and brings those moments into study activities

Besides connecting these two domains, we can also strengthen each of them. Our AI suggest tractable ways for Sam to “just dive in” to a new interest, and helped Sam build connections with a community of practice.

Finally, when we’re spending time in explicit learning activities, let’s make sure that learning actually works. Our AI creates a dynamic vessel for ongoing reinforcement it varies over time so that the knowledge transfers well to real situations. And it doesn’t just maintain memory—but increases depth of understanding over time.

Two cheers for chatbot tutors #

Most discussion of AI and education at the moment revolves around the framing of chatbot tutors.

I think this framing correctly identifies something really wonderful about language models: they’re great at answering long-tail questions… if the user can articulate the question clearly enough. And if the user’s trying to perform a routine task, chatbot tutors can often diagnose problems and find ways to get the user unstuck. That’s great.

But when I look at others’ visions of chatbot tutors through the much broader framing we’ve been discussing—they’re clearly missing a lot of what I want. I think these visions also often fail to take seriously just how much a real tutor can do. In large part, I think that’s because the authors of these visions are usually thinking about educating (something they want to do to others) rather than learning (something they want for themselves).

Now, a sad truth about the world is that postdocs and graduate students are incredibly underpaid, so it’s surprisingly affordable to get an expert tutor for a technical topic I care about.

But if I hire a real tutor, as an adult, to learn about signal processing, I’ll tell them about my interest in brain-computer interfaces, and I’ll expect them to ground every conversation in that purpose. My goal isn’t to “learn signal processing”, it’s to “participate in the creation of BCIs”. Chatbot tutors aren’t interested in what I’m trying to do; there’s a set of things they think I should know or should be able to do, and they view me as defective until I say the right things.

If I hire a real tutor, I might ask them to sit beside me as I try to actually do something involving the material. They can see everything I’m doing, see what I’m pointing at. If it’s appropriate, I can scoot over, and they can drive for a minute. By comparison, the typical conception of a chatbot tutor lives in a windowless box, can only see whatever’s provided on scraps of paper passed under the door, and can have no effect on the outside world. My goal is to dive in, to immerse myself, to start doing the thing. But these chatbot tutors can’t join me where the real action is. So interactions with them create distance, pull me away from immersion.

If I hire a real tutor, we’ll build a relationship. With every session, they’ll learn more about me—my interests, my strengths, my confusions. Chatbot tutors, as typically conceived, are transactional, amnesic. Now, we could fix that as context windows get longer. But that relationship is also important to my emotional engagement. If I view conversation with my tutor as a kind of peripheral participation in the community I’m hoping to enter—an interaction between novice in the discipline and mentor in the discipline—then tutoring will become just part of doing the thing. But if my interaction with my tutor is transactional, that will tend to make my tutoring sessions feel like “learning time”, separate from doing the thing.

Finally, people talk about how Aristotle was a tutor for Alexander the Great. But what’s most valuable about having Aristotle as a tutor isn’t “diagnosing misconceptions”, but rather that he’s modeling the practices and values of an earnest, intellectually engaged adult. He’s demonstrating how and why he thinks about problems. His taste in the discipline. The high-growth periods we love transform the way we see the world. They reshape our identity.

In my demo earlier, I showed a chatbot, but it didn’t really work like most “chatbot tutors” I see described. It focused all its actions on the user’s interest, rather than bringing its own agenda. It wasn’t trapped in a little text box—it could see and take action in the context of authentic use; it could communicate through dynamic media. It had a deep memory, drawing on everything you’ve ever written or seen.

So in some ways, the system I’ve shown is more like a real tutor. But in my ideal world, I don’t want a tutor; I want to legitimately participate in some new discipline, and to learn what I need as much as possible from interaction with real practitioners.

I view the role of the augmented learning system as helping me act on my creative interests, ideally by letting me just dive in and start doing, as much as possible. That will often mean scaffolding connections to and interactions with communities of practice.

A note on ethics #

One theme for this Design@Large series is the ethics of AI and its likely enormous social impacts. Let me say: I’m tremendously worried about those impacts, in the general case. I’m worried about despots locking in their power, about lowering the bar to bioweapons, about economic chaos. I wouldn’t feel comfortable ethically with researching more powerful frontier models.

But within the narrower domain of learning, my main moral concern is that we’ll end up trapped on a sad, narrow path. A condescending, authoritarian frame dominates the narrative in the future of learning. I’ll caricature it to make the point: with AI, we can take all these defective kids that don’t know the stuff they’re supposed to know, and_ finally get them to know it_! You know: personalized learning! The AI will let us precisely identify where the kids are wrong, or ignorant, and fix them. Then we can fill their heads to the brim with what’s good for them.

The famous “bicycle for the mind” metaphor is better because it has no agenda other than the one you bring. It just lets you reach a wider range of destinations than you could on foot. And it makes the journey fun too, particularly if you’re biking along with some friends. The bicycle asks: where do you want to go?

Of course, that question assumes your destination is well-known and clearly charted on some map. But those most rewarding high-growth experiences are often centered on a creative project. You’re trying to get somewhere no one’s ever gone before—to reach the frontier, then start charting links into the unknown. Learning in service of creation. It’s a dynamic, context-laden kind of learning. It’s about more than just efficiency and correctness. More than just faster gears on a bike. That’s the kind of learning I feel an almost moral imperative to help create.