Reflections on 2020 as an independent researcher

2020 was my second year as an “independent researcher.” I’m grateful for the freedom that strange job title entails, but it’s certainly not well-defined. I’ve needed to grope around in the dark for patterns and structures which pre-existing institutions and roles would ordinarily provide. To kick off 2021, I’ll share some of what I’ve learned, as well as of the outstanding questions which seem most pertinent. These observations are necessarily quite personal, but I hope they’ll be of interest or use to others considering similar paths.

1. Why work independently?

I’m not interested in independence for its own sake. I’m interested in inventing environments which significantly expand what people can think and do. That aspiration is what drives my work, rather than a particular title, role, or practice. When I use phrases like “independent researcher” to describe my work, the title is a loosely-held shorthand for what I really value: freedom of inquiry.

For that matter, I’m skeptical that “independent researcher” is a stable or desirable long-term identity. Independence offers freedom, but it’s also quite limiting, as I’ll discuss in more detail later in this essay. If the work goes well, an independent researcher will likely find compelling opportunities to evolve into some higher-leverage institution—a studio, a foundation, an academic center, a business. If the work doesn’t go well, most independent researchers would have trouble staying afloat.

In my case, the aspiration isn’t just to solve the object problem of, say, forgetting what you read. I want to more deeply understand the properties of enabling environments—principles of operation, design procedures and patterns, relationship to individual and social cognition—to foster a community which routinely invents new environments of this kind. Field creation will almost certainly involve institution creation. But my understanding is too weak right now to see much further.

Why not start a startup?

I understand theories by making software, and I live in San Francisco, so people often expect that I’m planning to launch a startup. But my interests are misaligned with a startup’s fundamental drive: growth. I’m interested in generating insight, not in generating growth, except insofar as growth is necessary to understanding the ideas I’m trying to explore.

Some companies figure out how to align these aspirations so that marginal revenue/usage enables marginal fundamental insight, which enables marginal revenue/usage, and so on, in a virtuous cycle. Pixar is a good example. Cutting-edge graphics research enables new kinds of storytelling, which in turn funds more research. To be sure, many startups do uncover fundamental insights, but usually as an inconsistent means, rather than as an end. A steady loop like Pixar’s is quite rare. You need a specific theory about why a given business model is connected to a given type of insight generation. You also need to explain why marginal insight remains an ongoing prerequisite to marginal business, rather than a “nice to have” which can be cut when convenient. I don’t have a theory like this for my own work yet. Such flywheels are particularly rare in my domain, since novel interface ideas are typically public goods. Their development might require significant investment, but once created they can often be copied cheaply by others, limiting returns to the inventor.

A related question I’ve had to straighten out for myself: am I really aiming for insight, or for impact? Is my goal only to invent such environments—or also to operationalize, scale, and spread them? Well, it’s true that my work is use-inspired; I identify more with applied researchers than with basic scientists motivated purely by discovery. So I wouldn’t want to work on a project without the possibility of transformative impact. But so long as I have some persuasive theory of how that impact could happen, I prefer to focus on producing insight through prototypes. I’d rather let others operationalize those insights into scaled products.

To put this another way, I’ll invoke a common trope about startups: “ideas are cheap; execution is what matters.” It’s a decent if overstated rule of thumb—but not because new ideas are unimportant. Startups are fragile. They usually focus on niches where execution is the primary factor because they have to. They tend to die if they tackle a niche which continuously demands both outstanding execution and also deep, original insight. This lens suggests a useful way to frame my goal: developing ideas far enough that they become “obvious,” the banal fodder for half a dozen companies in a future YC batch.

Another key misalignment makes me hesitant to consider a startup: culture. Tech culture is different from research culture, and I’m already quite overweight on tech culture. Anyone working in an industry for a while tends to adopt elements of that culture—its processes, its norms, its values, its tacit knowledge. Much of this is incredibly valuable, of course, but these norms also create constraints.

For example, tech culture is calibrated to a much faster pace than research culture. A “huge project” for a Silicon Valley tech person may be a year or two long; a “huge project” for a researcher may last a decade. Persistence with a difficult problem may require tens of hours for a tech person and hundreds (or thousands) of hours for a researcher, no matter how quickly try to work. It’s not that the tech people are constitutionally lazy or something like that: in industry, it usually is, in fact, a bad idea to spend many hundreds of hours thinking about a single problem. Better to create an 80/20 solution or try a different approach. But foundational insights often do require more patient, focused thought than heuristics from tech culture would naturally encourage. Coming from the tech industry, my expectations around the pace of progress are often seriously miscalibrated for many problems I’m tackling. I’ll feel like I’ve been banging my head against a question forever, but it’s only been a few tens of hours. That’s nothing! With this mindset, I’ll miss the results I seek and, as a bonus, drive myself nuts. I’m working to become much more comfortable slowing down.

Why not become an academic?

If I’m interested in freedom of inquiry and focused on generating insight, why not join academia? There are some boring stock answers: publish-or-perish, the grant treadmill, overbearing administrative responsibilities, conservatism, etc. But the real reason is my choice of field. My goals, values, and practices align poorly with the academic discipline which would most naturally host my work, human-computer interaction (HCI). If, in some alternate universe I were interested in a different topic, there’s a good chance I’d have become an academic.

That’s a dispassionate way to put it. A subjective and inflammatory way to put it is that I feel academic HCI discourages vision and imagination. Part of the trouble seems to be that the field’s trying too hard to be a science. It emphasizes an empirical approach, often producing elaborate artificial evaluations of uninteresting systems. Peer reviewers seem to reward analysis and data over ingenuity and compelling direction. The field disincentivizes building systems significant enough to explore new paradigms; published systems are rarely driven by a serious context of use. I read the major conferences’ proceedings every year, yet I learn much more about HCI from studying game designers and idiosyncratic Twitter tinkerers. Of course, there are a few researchers who do great work in spite of the field’s challenges. It’s hard not to be inspired by people like Hiroshi Ishii or Ken Perlin. And I should be clear that these are comments about the field, not about the individuals in it, who have consistently struck me as kind and well-intentioned. The headwinds just seem too strong to justify.

I’ll share one more story about the field. I noticed a professor’s name on several papers I enjoyed, so I invited them to chat. We had a friendly, wide-ranging conversation about topics in the field. Then at one point, I asked: “How do you balance pressing your own long-term research agenda in your lab with supporting the inquiry of your grad students?” They replied with some consternation: “Oh, no no, you have it wrong. I view my primary role as helping students pursue their own research projects. I’m not trying to push any long-term agenda of my own.” I suspect they exaggerated their stance here. Beneath the surface, I can see some consistent theories threading through the students’ papers. But if all professors really operated according to this one’s belief, we can see the problem that would be induced. The entire field would consist of nothing but student work, without any venue for senior researchers to develop an idea of their own over time. I’m sure that’s not actually what’s happening, but qualitatively, the sense I get reading the major conference proceedings isn’t so different. It feels like skimming a sea of churning froth—tiny isolated studies rarely accreting into a broader current.

I criticize academic HCI not out of ill will but out of genuine perplexity. I honestly don’t understand why the field behaves as it seems to behave. I’d really love to be wrong. If you think I’ve misunderstood something, I’d love to read your comments. Maybe the problem is that I’m actually trying to start a field which doesn’t exist yet, so of course HCI looks misaligned. Maybe this is my version of Bryan Caplan’s sour grapes. Maybe I’m too arrogant or closed-minded.

So I work independently. Not because that’s an ideal arrangement, but because I don’t see a good alternative. I don’t yet know how to create or join an institution which would enable better work. Part of the trouble comes from working in a proto-field, without methodology or principles solid enough to effectively support a pipeline of new investigators. In fact, I don’t understand yet my own projects well enough to effectively coordinate a large team around them, though I could certainly put a few more hands to good use. The most concrete incremental constraint is, of course, funding. Let’s talk about funding.

2. The unexpected success of crowdfunding research

When I left Khan Academy in early 2019, my (very understanding) wife and I made a rough plan: in 2019, I’d focus on the work and avoid thinking about funding at all; in 2020, I’d figure out some plan for sustainability and begin moving towards it; hopefully by the end of 2021, we’d stop burning cash. My collaborator Michael Nielsen suggested we set up a Patreon to solicit funding for our work, and I agreed, not thinking much of it. He’s now moved on, but I’m quite grateful to him for that early nudge.

Less than two years later, my patrons have crowdfunded roughly a graduate student’s fellowship grant. It’s not lucrative, but it’s enough to cover my living expenses. That’s an important milestone! So long as this income stream continues, my runway has been extended indefinitely—or at least until I start getting nervous about not being able to save. My goal was to end 2020 with a plan for how to eventually fund my work, but I’m astonished to now find myself ending 2020 with solid funding in hand.

Is this a model which other independent researchers could use? My story doesn’t necessarily generalize, but I’ll share some observations which might be useful to others interested in experimenting with crowdfunded research.

Growing a crowdfunded research grant

First, we should examine the dynamics of growth and churn. The funding must be stable if it is to be a viable source of independent research. In Technology and Courage, Ivan Sutherland describes courage as one of the key ingredients for research and notes:

I find that I have only so much room for taking risks. When I can reduce the risk in some places in my life, I can more easily face risk in other areas. I provide myself the courage to do some things by reducing my need for courage in other areas.

This certainly matches my experience, not just with Patreon but with marriage, home ownership, investments in well-being, and so on.

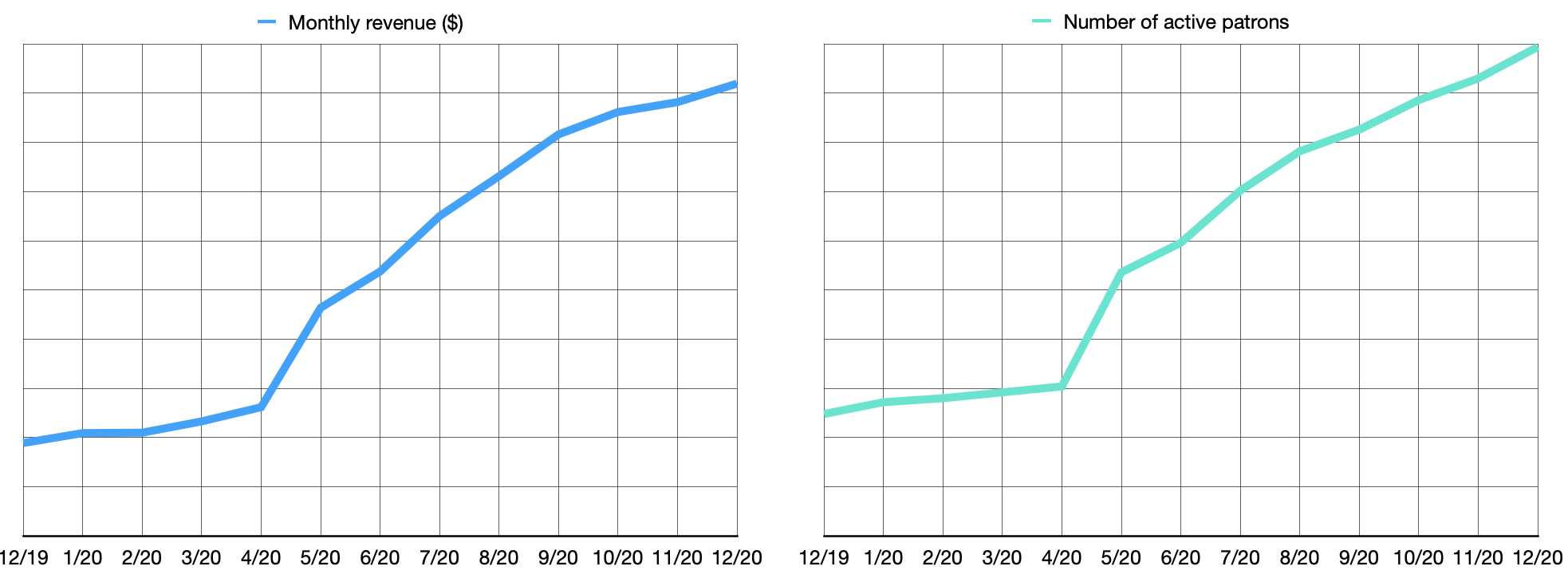

These charts depict the shape of monthly revenue and membership count growth over 2020 (the differences are due to volatility in the distribution of patrons’ pledge sizes):

On the whole, then, my Patreon experience has been characterized by modest but steady growth. To understand how stable the funding is, we should understand the dynamics of churn, which these charts don’t depict. The story there looks decent: monthly new patron rate (median, 25–75th %ile) was 9% (8–15%); monthly departing patron rate was 3% (2–4%). This suggests reasonable stability, though departure numbers should increase over time since the Patreon is new, while new patron growth may decline as I saturate my interested audience.

Annual billing has been a helpful boon for me. Roughly a quarter of new patrons elect to pledge on an annual basis. Assuming steady revenue growth, then, these patrons’ annual commitments let me fast-forward about three months into the future along my growth curve. Annual pledges also offer a helpful extra measure of stability.

On my Patreon, I offer three funding tiers: $5, $20, and $100. The tiers are mostly arbitrary for now—the only difference is that the $100 tier comes with public attribution (which no sponsor seems to care much about). But the tiers give people a way to modulate their support according to their interest and capacity. I’m quite happy with how the price mix has worked out. Most of my revenue comes from $5 members, while a smaller number of more generous sponsors’ contributions boost my funding considerably. In aggregate, that mix generates a grant large enough to live on, while freeing me from worries about any individual funder. This does wonders for my peace of mind. At Khan Academy, we were often quite dependent on a small number of huge-value donors, and we’d regularly fret about appeasing them; when one would decline to offer another grant, it would create tremendous stress. The “grassroots” situation creates a much healthier interpersonal relationship with funders, some of whom are personal friends—I’d hate for anyone to feel like they need to keep funding me out of some sense of guilt.

Patron growth appears to be roughly linear, but you’ll notice a discontinuity in the slope of the graph around May. That’s when I decided to try sharing more exclusive writing with patrons. This does seem to have worked as an enticement, though I’m actually not sure how important exclusivity is. I expect the articles drive new patron growth in part because they create repeated opportunities for others in patrons’ networks to stumble upon my work. Is the higher rate of growth because people want to unlock the paywall, or because articles create traffic? I hardly promote the Patreon at all—I’m not yet sure how to do that in a way that makes me feel comfortable—so this type of traffic may be important.

Researching in public

One surprise of crowdfunding research has been the pleasure of building a closer relationship with a community of people enthusiastic about my ideas. But to do good work, I mostly need to avoid thinking about funding and funders. The promise of ongoing exclusive content creates some tension, then. Unlike a typical paid newsletter or blog, funder-exclusive writing is a secondary by-product of my primary work. In this way, I’m not a traditional “content creator.” Sometimes I catch myself thinking in terms of what I’ll write or report next to my funders. That’s not good. Such a mindset, taken too seriously, encourages shallower work designed to appease others. Also, I’m human, so I naturally want to report successes. But this can create the same pressures which exist in scientific publishing: short-term-ism, conservatism, publication bias, harmful over-claiming. In research, it’s terribly important that you be brutally honest with yourself. I don’t think it’s possible to craft marketing-like messages about your “great progress” without closing your own eyes to what’s actually happening—which means you’d better be brutally honest when talking to others about your work.

As an antidote, I’ve tried to engage in what Michael has called “anti-marketing”. That is, to make a point of focusing publicly on the least rosy parts of my projects—what’s confusing, what’s frustrating, what’s not working. It’s hard to do consistently, but when anti-marketing is the goal, then interesting challenges become something positive: useful fodder for public conversation, rather than something to be swept under the rug. I suspect it also builds a deeper, more authentic relationship with an audience.

More broadly, I’ve experimented this year with a mindset I’ve been calling “working with the garage door up.” I try to share rough, ongoing artifacts from my process, including the working notes where I do most of my daily thinking. This has worked quite well when I adopt the right mindset—that I’m sharing objects made as part of my primary work, rather than things created specifically for publication.

The practice generates more conversation and serendipitous inbounds “for free.” It’s worth noting that in most ways, unusual inbounds are a better leading indicator for my work than page views or other more traditional metrics. Popular projects might garner a lot more mass attention but a lot less attention from unusual, singular people. Those people often introduce surprising (and more meaningful) insights and opportunities.

Apart from potential distraction and distortion, there’s another subtle issue with talking to a broad audience about ongoing research. The clearest, most familiar parts of your ideas are the ones which you’ll have the easiest time communicating and which your conversation partner will have the easiest time grasping. Often, those elements are already somewhat mainstream or even clichéd. Others are likely to have lots of cached thoughts around such ideas, and they’ll tend to be interpreted incrementally.

But if you’re doing something original, the most interesting aspects are the ones which others—and you!—understand least well. Particularly early on, you may not be able to articulate the new element you’re reaching for very clearly. It may just sound like an unusual adverb choice or an innocuous-seeming qualifier. Others’ replies will tend to emphasize the most mainstream elements, since they may not notice or know how to react to the aspects you least understand. Such conversation will often drag you back towards the mainstream. It’s a kind of “regression to the mean” for ideas.

Great colleagues and collaborators can take more active steps to mitigate the issue. For instance, if Michael hears me talking about some idea that seems fairly banal on the surface, he’ll deliberately tug at the vague spots where I’m straining to reach past typical interpretations. This was part of a broader practice he called “listening for enablement.” My Khan Academy research colleague May-Li Khoe would respond to my poorly-understood ideas by riffing in unpredictable directions. Her sketches would often explore wildly different paths, but those vivid reactions often helped me understand my own inklings better. Unfortunately, I’m not yet sure how to avoid the regression problem when discussing ideas regularly with a broad audience.

What are patrons buying?

Free web sites often have a “donate” button with language like “if you enjoyed this (free) content, please consider showing your appreciation with a donation.” That’s how we thought of Patreon initially: roughly like a tip jar. But in a patronage model, people fund the work in an ongoing fashion. The tip jar model doesn’t explain that behavior very well. Why donate repeatedly over time out of gratitude for past material?

In my interactions with patrons, I’ve been surprised to find that altruism is rarely the dominant force. Patrons mostly don’t think of themselves as paying for consumption of past work; they’re buying into production of future work.

From this angle, it may make more sense to think of the production of the work itself as a product. What are patrons buying when they buy that product? In its most compelling form, a patron’s purchase causes future work to be produced which would not have been produced without it. Perhaps without that patron’s contribution, the creator must spend some of their time freelancing to pay the bills, so their projects were limited in scope; but with that patron’s contribution, the creator can work full-time on much more ambitious projects. Or maybe they can hire a freelance artist to illustrate their game, etc. This is like a Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign, except in an ongoing fashion instead of for a one-time effort. In my current situation, marginal funds buy something subtler: growing confidence and stability; freedom from foundation or investor appeasement. As funding continues to grow, marginal funds will likely buy contractor time to expand my scope.

In December of 2020, I asked my patrons to briefly explain why they support my work. Roughly a quarter of my patrons wrote back. The vast majority framed their motivations in terms of supporting production of future work. Some people quite specifically want to use a prototype I’m developing; others just want to see certain ideas developed further. About a third framed their funding in terms of “people, not projects,” expressing general confidence that I’ll do interesting work. Naturally, that’s my favorite kind of support. After this cluster of answers, the distant second most common motivation was access to the behind-the-scenes content.

I considered asking patrons to pick their top couple reasons from a pre-authored list, but I thought it would be more interesting to read open-ended responses. I’m glad I did! I wouldn’t have included any of the following motivations, but each was expressed by >10% of respondents:

- patronage creates a feeling of being “on the edge” of something new

- participating in the experiment of crowdfunding research

- seeing my work “up close” is a source of personal inspiration

- wanting to support “tools for thought” in general (rather than any of my specific projects)

Understanding all this helps me better frame how I describe and relate to the Patreon publicly. For example, relatively few readers cited exclusive content as an important motivation, but it clearly accelerated the growth of funding. Seeing these responses from patrons, I dug into the data and noticed that after I started sharing extra content with patrons, patron drop-off rates fell roughly by half. My current theory is that for many patrons, this insider content is important mostly because it reinforces the (approximately true) impression that their support is creating marginal production, which is by far the dominant motivation people cite.

My path to sustainability

How repeatable is my modest success with crowdfunding? Could others follow this path? I can’t know, of course, but it’s worth articulating some of the factors which may have been essential. At a high level, my story is one of leveraging career capital from the tech industry. As Adam Wiggins suggests, I suspect it’s possible for more tech people to do this once they have some years under their belt.

First and foremost, I was in a position financially to draw no income for (as originally planned) several years. In terms of the general population, this is a very unusual and fortunate position! For many tech workers, though, it’s not a terribly outlandish goal. Most of this capital came from five years spent at Apple: joining Khan Academy (a non-profit) cut my income by two thirds. San Francisco is quite expensive, but we’ve lowered our costs by owning rather than renting our home, which of course also required capital. My wife’s generous understanding was unusual and essential. Practically speaking, though, it helps that she’s a doctor. Having trained from 2011 through mid-2020 (medicine is wild!), she recently began her first “full” attending position, now at last with plenty of earning potential of her own. Also, we don’t have (or plan to have) kids; our mortgage is our only debt; our families don’t need our financial support. It’s a fairly ideal situation financially, except for the San Francisco part.

I should mention that there was another straightforward path for me (and for many other tech workers) which wouldn’t have required crowdfunding at all. Before I left Apple, my plan was to save enough that I could quit and pay myself a grad student’s stipend from the interest indefinitely. It would have taken another five years or so, depending on my diligence. That seems very achievable, though I was so uninspired by the work at Apple at that point that it might have done some permanent damage!

While I’d planned to live without income, I avoided burning through savings by becoming the lucky recipient of an Emergent Ventures grant. It covered my first year’s expenses. I would certainly recommend Emergent Ventures to others trying to find a way to support their independent work. The application took only a couple hours; I enjoyed a half hour of thoughtful conversation with Tyler Cowen; they made a decision within a few days; my only obligation was to send them a few short reports. Emergent Ventures stands in delightful and courageous contrast to the intensely burdensome experiences I’ve typically had interacting with foundations. The grant successfully bootstrapped me: by the time the grant expired, my patrons mostly covered my expenses. Self-obsolescence seems like an ideal outcome for a philanthropic grant. I suspect this kind of bootstrapping would be quite important for many people to crowdfund independent work: patrons take time to accumulate, but the first few hundred donations aren’t enough to quit your job.

Finances aside, a few related career capital factors have likely been crucial to my progress. They may be important for others doing similar work.

First and foremost, I’ve had enough professional experience to build up a rare skillset. I can independently research, design, implement, analyze, and report on novel software environments. I’m certainly not a world-class graphic designer or literature reviewer, but being able to execute the whole end-to-end process myself makes an enormous difference. There’s also a matter of degree. Being able to prototype systems is important, but I’m comfortable rapidly building highly polished production systems, systems which can attract users organically and engage with serious, real-world contexts. I suspect one key challenge for academic HCI is that researchers often lack the skills (if the inclination) to design and execute consumer-quality software. Without those skills, many projects are trapped in toy contexts.

My past experiences have also yielded essential social capital. Most people don’t seem to care that I’m unaffiliated, but I suspect that’s only because I can introduce myself by saying I helped build iOS at Apple and led R&D at Khan Academy. Without some kind of strong social proof, it may have been hard to get anyone to engage seriously with my work. Along the same lines, my past work and writing has accumulated a modest but substantial online audience. I don’t need an academic journal or publisher to market my work for me because I can “publish” on Twitter. My audience isn’t large by “public intellectual” standards, but it’s enough to produce strong network effects which propagate the work quite broadly and prompt interesting inbound relationships. This same network is the source of most of my patrons. I don’t think I could have recruited this audience of funders without Twitter—at least not with such little effort and distraction.

So there seems to be some important path dependence to my career journey. If I’d tried to jump into my present work immediately, I’d lack many key skills; I’d work too slowly; I’d be distracted by promoting my work and marketing to funders. Maybe I would have made good progress despite these challenges. I’m not sure! But my experiences do suggest that many more “staff/principal”-level tech workers could successfully pivot to an independent practice.

I’m much less sure about this last point, but I suspect my work depends on time spent living in San Francisco. Prior to the COVID pandemic, most of my evenings were filled with conversation which reinforced a mindset of earnestness, intensity, disagreeableness, resourcefulness, and so on. Patrick Collison advises: “Figure out a way to travel to San Francisco and to meet other people who’ve moved there to pursue their dreams. Why San Francisco? San Francisco is the Schelling point for high-openness, smart, energetic, optimistic people. Global Weird HQ.” I think he’s right. Living here has changed me deeply. Probably other places would have had a similar (or a better?) effect on similar axes. For example, I like what conversation in Cambridge, MA does to my state of mind. But when I lived in Portland, OR, for example, the environment tended to emphasize a different set of values—community, craft, sustainability, enjoyment. I liked these values, too, but I suspect they would not so naturally reinforce my current work.

Can you absorb a scene’s values through the internet? I certainly did to some degree as a teenager living in Saint Louis. Social technology has only improved since then. In many ways, distributed networks like Twitter transmit values more fluidly than live interaction. But my sense is that bandwidth limitations in interaction are significant. There are depths which are hard to absorb without constant physical immersion.

3. Working alone

I may be working independently, but that doesn’t have to mean working alone.

Executing alone

I’m very grateful to have a modest and possibly sustainable source of funding for my work. But as pseudonymous blogger Applied Divinity Studies writes (after receiving an Emergent Ventures grant of their own):

I suppose the expectation is that I’ll just save the money or spend it on rent. The implicit assumption being that I have a burn rate, this defines my runway, and money is used to extend the time I have to continue to do what I’m already doing.

But that’s crazy. This isn’t how any ambitious person spends money, nor is it a path to long term growth. Surely there’s some way I can spend this money to actually do better work, earn more money, and grow exponentially? … Surely there’s something I can do with the money other than give it to my landlord?

I’ve been writing about a related metric in my work since 2018: how much capital do I feel I could productively deploy towards my goals (annually, say)? In early 2019, it was a few tens of thousands; now I’d put the number at a million or two. It’s still not a high number, but at least it’s climbing. The difference is that I now understand the work well enough to imagine how I could accelerate it with a team.

I also understand an enormous challenge I face in working alone, doing the type of projects I’m doing. I might be a jack-of-all-trades, but practically speaking, I worry that I can’t do good research if I’m also doing all the implementation work. The simple version of the problem is that there are prototype ideas which I don’t explore because it would take too long, and there are many concepts I’ve sketched yet haven’t had time to implement. But there’s a deeper problem here.

My approach requires developing new software interfaces which express insights, then studying those interfaces and their use to generate new insights, and so on. Michael and I called this “insight through making.” In practice, it’s quite difficult to think deeply about theories while in the midst of a significant software development project. They’re different states of mind. And it’s hard to build momentum on software development when spending much of one’s day in reflection, writing, and study. Worse: switching costs are high between software development and research thinking. I’ve not had much success when dividing my days or even my weeks into “building” and “thinking” blocks.

In March 2020, I wrote a list of research questions for the mnemonic medium, then embarked on building Orbit, which I planned to use to study those questions. Nine months later, I’ve made little progress on those research questions. I’ve mostly been building. At some point I’ll need to execute a “hard switch” back to thinking about those questions for a while, during which time it’ll be difficult for me to build anything significant for Orbit.

Maybe that’s fine. I just need to spend months at a time in one mode or the other, and I need to get more patient. But when I’m deep in software development, reaching flow on a daily basis, my mind narrows to a kind of tunnel-vision, totally fixated on the software systems and their problems. The problem isn’t just about escaping tunnel-vision in that moment. I’m worried that engineering mindset stunts my growth as a researcher (still quite nascent), even in the weeks following an intense period of implementation.

Another problem with cycling slowly back and forth is that feedback loops become too long. For example, in February, Michael and I published an experiment involving a new kind of spaced repetition prompt, an “application prompt” which we thought might help readers apply what they read. We’ve run some initial analyses and interviews around those prompts, but in truth we’ve learned surprisingly little about them since their introduction—mostly because I’ve been focused on building Orbit. A very reasonable criticism of my year is that I’ve built a grand new observatory before I’d come close to exhausting what I could see what the one I already had.

I understand at least some of my projects well enough to accelerate them through execution-oriented teammates. In 2021, I’d like to experiment with volunteer and (funding dependent) contract collaborators. It would be easy for coordination overhead to do net damage to my work—so this goal will depend on finding the right people.

Culture and scenius

I may not want to join academia, but I deeply envy a good field’s intellectual kinship. Solo engineering has fairly obvious limitations; solo research presents subtler problems. I’m grateful for intermittent conversations with others doing related work, but for the most part it’s not enough.

I want to be part of a rich scenius of serious, capable people doing full-time original research on enabling environments. I want to attend colloquia in which I’m regularly stunned by the ideas presented. I want peers who will candidly observe the limitations of my ideas, then work with me to improve them.

I don’t yet know how to make this happen. My proto-field has (hopefully) a proto-scenius: many part-time tinkerers, many startups doing research-ish work when they can spare the time. Funding is one limiting factor for a bloom of full-time work. But culture is another. This scene, as far as it exists, mostly draws its norms and values from tech culture—just as I originally did. I like the influence of arts culture on this scene, supporting a more expansive, playful design orientation. But I worry that we need a significant injection of research culture to support the patient, probing, self-critical work which can yield transformative insights.

I recognize the irony in calling for more research culture after earlier maligning academic HCI. But my problem is with norms and goals at the field level; many individuals working in it could still provide great influence. And we could draw on researchers in other fields, as I’ll describe in the next section.

I’d like to focus more effort on this problem in 2021.

Serious contexts of use

The most serious problem for me in working alone is that it means I lack a serious context of use. I’m building tools for tools’ sake. As Michael and I described elsewhere, this is one of the most common failure modes for work like mine.

The Apollo program created countless powerful scientific and engineering tools, but the point was putting people on the moon (and showing up the Soviets). Likewise, when Pixar created its revolutionary animation tools, many teams had been working on computer graphics for years, but Pixar’s systems emerged from a zealous pursuit of a storytelling dream. Mathematica is great because Wolfram built it to help with his own mathematics research. And so on.

Practically speaking, such contexts provide deeply meaningful feedback. Many critical insights about a prototype system will only emerge in the context of a serious creative problem that’s not about the system itself. But perhaps most importantly, these projects also provide the intense personal connection which makes great work possible.

Adjacent to my work, there are many “explorable explanations” which attempt to explain a subject through novel interactive media. Some of these articles are quite striking. But most are primarily motivated by the author’s interest in the experimental medium. Most authors’ skills lie primarily in building interfaces, rather than in whatever discipline they’re trying to explain. These authors’ medium ideas are limited by their lack of domain expertise and domain motivation. By contrast, it was important that Quantum Country had a serious context of use: to help earnest students learn all the fundamental principles of quantum computing and quantum mechanics, as well as several applications. This richer context was possible because Michael is a pioneering quantum computer researcher.

So one recipe for insight through making might be deep collaboration between some colleagues focused on some serious domain problem which might benefit from augmentation (“tool-users”), and other colleagues looking to use that context to drive the creation of new environments (“tool-makers”). My plan for 2020 was to start an experimental media studio along these lines with Michael, but I shelved that approach when his plans changed, since it depended on his skills as a synthesist. I’ve spent the last few months building relationships with domain experts who might make interesting collaborators in a similar vein. It’s too early yet to declare success or failure, but this type of collaboration is not easy to establish.

What are the limits of independent research, and of independent funding? If independent research is a stepping stone, what new paths does it open? Is my position a fluke or an example? Can independent researchers be coordinated into a scene without traditional institutions?

I’m not sure how to answer any of these questions, but I’m grateful to be trying. Happy new year.

This essay was originally patron-only. I decided to make it available publicly a few weeks later after a number of emails from patrons who wanted to refer to it in public conversation.

Special thanks to my sponsor-level patrons as of publication: Adam Marblestone, Adam Wiggins, Andrew Sutherland, Bert Muthalaly, Calvin French-Owen, Dwight Crow, fnnch, James Hill-Khurana, Lambda AI Hardware, Ludwig Petersson, Mickey McManus, Mintter, Patrick Collison, Paul Sutter, Peter Hartree, Sana Labs, Shripriya Mahesh, Tim O’Reilly.