Three years of crowdfunded research

January 2023. Part of “Letters from the Lab”, a series of informal essays on my research written for patrons. You can also listen to this essay (19 minutes).

I’m an independent researcher. That’s an unusual position, for sure—but what’s even more unusual is that 2022 was my third year as a crowdfunded independent researcher. My primary income is, and has been, a membership program. Most researchers answer to a few grantmaking committees; I answer to hundreds of internet strangers.

The funny thing is that they don’t quite feel like strangers anymore. In 2020, I viewed my membership program simply as a funding source, a way to pay my bills without contorting myself through grant applications. But slowly, spontaneously, the program has grown into something much more central and vivid in my creative life. Now it’s a compelling rhythm, a context that scaffolds and energizes my work.

Three years in, the membership program is still evolving, and so are my feelings about it. But here’s a snapshot for the new year. How has crowdfunding shaped my work? How do I relate to it, emotionally? How might it evolve in the future? I’m sure my experience won’t generalize, but perhaps it’ll be of interest to others considering similar paths.

High-context listeners

Research often has a slow tempo; projects can span years. My membership program has created a faster loop inside the slower one, a space eager to observe the work as it unfolds. I’m mostly working on one enormous project, yet membership creates a context in which I can usefully publish quite regularly; this year: working prototypes, essays on projects and methods, scripted demo-talks of new designs, hours of audio.

I worried that writing for patrons would feel like making dutiful “reports”. In 2020, it did feel that way. But that was my fault. My emotional stance changed as I had more conversations with members and began to understand their mindsets. They aren’t program officers, looking for evidence of a productive grantee. Most are curious creatives, looking for an intimate view of an unusual life, a challenging creative process. I’d initially thought of members’ desire to “see behind the curtain” in a demanding, stressful way: people want me to finish prototypes they can use—sooner, faster! In reality, members’ comments generally suggest that they want to see what it’s like to do this strange thing I’m doing. They want to see the parts spread out on the table, see me move my hands, share in the moments when something finally clicks, however provisionally. Magic is exciting, but sometimes it’s even more exciting to dispel something magical, to glimpse the gears.

That’s fine for members. But what do I get out of this? The way I escaped the essay-as-duty frame is by recognizing: here’s a context which pushes me to think carefully about some aspect of my work. Here’s a context which delivers a meaningful hit of creative gratification—reliably, right now—while my long research project rolls unpredictably onward. With that frame, essays for members become a creative “move” in my toolbox. Choose a question, a detail, a practice, an idea; write what I think I think; discover much more in the process. These essays become part of actually doing the research, not an added burden.

All this sounds like typical (good) advice: writing helps you think! Write more, and you’ll think better! That’s true, but what makes the membership program different for me is that I’m writing for extremely high-context listeners. Most of my readers will have read tens of thousands of words about my projects. Probably more than a hundred of them have read a hundred thousand words about my recent work. (That’s… a bewildering sentence!) It means I can jump straight to the edge of the work, straight to what I’m thinking about. When I talk to a general audience about my research, I spend most of the time just providing background. Most of the response I get is stuff I’ve heard dozens of times before. By contrast, my patrons mostly want to meet me where I am, and that utterly changes how I relate to the writing.

Could you focus your writing on an extremely high-context audience without a membership program? I’m sure that many authors manage it, but it’s emotionally tough for me as a writer. Newsletters are ubiquitous these days. Subscribing just isn’t much of a signal. I’m on plenty of mailing lists I don’t really care about, and you probably are too. Most newsletter authors will need to assume a wide distribution of reader investment. Sure, one could choose to write for a tiny subset of that distribution at the far right tail, even if it means alienating most of your readership… but that requires steely grit as an author. On the other hand, if you’re one of my patrons, you’re one of a few hundred people who are directly funding my research. You’ve given me an unusually powerful signal of interest, and that makes it easy for me to communicate accordingly.

That strong signal of interest also makes it easier for me to write honestly. Most papers and public writing about inventions (understandably) contain a substantial dose of marketing. Consciously or not, authors are trying to convince their readers that they’ve created something novel and valuable. The work’s limitations are usually diminished, confined to a few paragraphs at the end. That might be appropriate for “finished” work, but it’s certainly the wrong mindset for writing-as-thinking about live projects. I want to focus my “intermediate” writing on what’s not working, tantalizing details I don’t yet understand. And, for a high-interest, high-context audience, I feel safe doing just that.

Here’s the bittersweet part. These regular high-context listeners are precious because they simulate some of what I’d have in a good university department, with a good lunch table and a good seminar series. I don’t have those things. I cobble together what I can through walks with peers around San Francisco, long email threads with distant colleagues, and these essays for my high-context members. I’m grateful for those venues, but I recognize that they’re a poor substitute for top-notch everyday social immersion. Still, all this is more than I had a couple years ago, and I’ll be experimenting with a few new mechanisms this year.

Another surprising way that my membership program simulates being at a university: I get the chance to help others grow. Many aspiring inventors have told me they’ve found it incredibly instructive and enabling to see my gears turn, to hear me reason about problems, to see me break down projects and make progress. I get it. My own growth has depended enormously on watching colleagues do those things in person. It’s gratifying to indirectly scale this sort of tacit knowledge, at least in some part. Sure, I hold office hours, and I write some explicitly didactic material—but upon reflection, I don’t think these are nearly as valuable as simply showing what I’m doing, in lots of detail.

Not being a “content creator”

You’ve probably read breathless essays about the “creator economy”. Thousands of writers earn an independent living through newsletter subscriptions. Many popular podcasts are available only to paying listeners. The membership platform I use, PatreonA warning for others considering crowdfunding: I wouldn’t recommend Patreon to new creators. Patreon locks you into their platform; there’s no way to migrate without requiring every member to re-enter their payment details. If I were starting now, I’d use Ghost or Memberful instead. Both allow payment migration to other platforms. I’d migrate if I could—Patreon’s presentation of my work is embarrassingly clunky, and I can’t change it. I’ll migrate at some point, but it’ll be a huge hassle, and I’m putting it off. Meanwhile, my members pay them thousands of dollars in fees per year., began as a way to support musicians and video creators on a pay-per-creation basis. All these examples make a simple pitch: you pay a recurring fee, and in exchange you get access to a steady stream of exclusive new content.

Now, in the previous section, I discussed the regular essays I write for patrons. But unlike the author of a subscription newsletter: I’m not trying to be a “content creator.” Access to those essays is not what I’m selling—or at least not what I intend to sell. I’m a researcher, trying to invent tools to give us new cognitive and creative powers. For a newsletter author, published writing is the primary activity. But my essays are secondary, intermittent byproducts of the central work which consumes my days. I can’t (and don’t want to) compete with a full-time writer.

My pitch to members is less transactional. It’s more like patronage in a historical sense. My work is a public service, and my primary outputs are available for free. Becoming a member is like being a tiny grantmaker. It’s saying: “Yes, for the price of a monthly latte (or whatever), I’d like to help enable progress in the domains Andy’s pursuing.” Now, that’s a fairly pure relationship. It’s basically an elaborate donation box. But then I muddy the waters: as a bonus, I say, you’ll also receive regular behind-the-scenes essays, events, early prototypes, and so on.

In past surveys, patrons overwhelmingly reported that their primary motivation for becoming a member was to enable my research. Only a small fraction said that access to exclusive content as a primary factor. But exclusive content sure does seem to matter! In early 2020, when I framed my membership program as a purer donation box, visitors were several times less likely to sign up and stick around. How should we square this?

The best explanation I have comes from fellow independent, Craig Mod: “This membership program is, at its core, like a mini NPR — of course, there are perks, but the main reason to become a member should be: Craig, ya weird bird, I want to see more of your work in the world.” I remember watching PBS membership drives as a kid. There was a full-time team making this happen, and they clearly thought perks were essential. On stone tablets given from on high to all the presenters: perks! Gotta shill the perks! Yes, with the support of viewers like you… but—the boxed DVD sets and the commemorative caps, every ten minutes! Membership costs much more than the merchandise, so it’s still mostly a donation, yet the perks obviously helped close the deal.

But I’m also a member of my local modern art museum, SFMOMA. Membership costs about four times the price of a regular ticket; members get free tickets to the museum for themselves and a companion. So if you go at least twice with a partner, membership pays for itself. The museum bravely tries to frame this like NPR/PBS: please support the non-profit museum… and, as a perk, you’ll get these free tickets! I like SFMOMA a lot, but if I’m being honest, I’ll confess that “supporting the museum” represents 0% of my membership motivation. It’s too diffuse a public good. I visit a lot, and I’m really just purchasing tickets through membership.

So is my membership program like NPR or like SFMOMA? Mostly a donation or mostly purchasing the perks? I’m quite clear whenever I write about it that prospective members should think of it as primarily supporting my research. But I feel I’m fighting a rising cultural trend. Subscription-gated content is everywhere now, and growing. I’m in the minority here, running a weird NPR-style membership program. If someone pays for five content creators’ subscriber-only content, then joins my program, it’s hard to imagine that “content creator” expectations wouldn’t start leaking over to me, if only subconsciously. I feel this “content creator” pressure, in some inchoate way I can’t quite describe, and it worries me. I do my best to ignore it, but I have to imagine it leaves a subtle influence.

Maybe my best defense is a goofy one. If you think of me as a content creator, my monthly membership fee looks like a “bad deal” by comparison to other content creators. So you’ll self-select out. Ta-da!

Events

One benefit of running a niche membership program is that I’ve gathered together a bunch of people with overlapping niche interests. My sense is that it’d make sense to help these people connect. I held about two dozen events for members this year, across a variety of formats. My motivation here has been partly selfish: maybe I can help grow the “scene” around my research, foster some future peers or collaborators?

Since I knew many members were working on novel user interfaces themselves, I began by hosting open office hours. I’d answer questions, generate ideas, host design crit, and so on. Perhaps a dozen members gamely brought their work in progress, and it was a delight to facilitate discussions of others’ projects. After ten sessions, though, this pool had mostly dried up. Just not that many people were working on big projects of their own appropriate to share in that venue.

I’ve had somewhat more luck with a series of research seminars focused on a specific notable paper or talk. These are great for me, since I choose a work I’d like to understand more deeply. I bring notes for discussion, but the other attendees always have lots of good questions and observations. Key to this is a strong norm: I ask people only to attend if they’ve actually read the paper or watched the talk. So the discussion ends up intense and high-signal. It’s also helped to invite attendees from outside my membership program who have special insight or interest in the work being discussed.

I’ve also held two “unconferences” for members. These don’t take much work for me to organize, since we hold them in Gather and members assemble the schedule. Like any unconference, sessions are informal and multi-format: demos, talks, workshops, problem-solving sessions, show-and-tell, etc. These events have been quite generative for me—particularly the second conference, for which I invited a few other small communities to join as well. Unfortunately, even in Gather, the all-important “hallway track” at these online conferences is much diminished. And since I was trying to help members connect, that’s a major problem. The COVID bloom of new remote social tools doesn’t seem to have solved it.

There’s one obvious related approach here I haven’t tried: creating an ongoing realtime discussion community, through tools like Discord, Zulip, or Discourse. I’ve joined lots of online communities on platforms like those, and they’ve never worked for me. They always end up feeling like a burden—one more inbox to check, another thing I have to keep track of—rather than a fount of joyful connection. Also, if I’m really trying to grow my “scene”, I don’t love the idea of a paywalled members-only discussion community. If we really care about good conversation, we want the community to include people who do good work and contribute good discussion. That set only partially overlaps the set of my patrons. I could add some layer of invitations, but I don’t want to be responsible for “playing host” on this scale. I continue chatting with others who have invested more heavily in these sorts of environments; maybe at some point I’ll find an convincing angle here.

Paying the bills

Friends aren’t quite sure how to frame the question. “So, how’s your crowdfunding… going?” What they really mean is: Andy, are you okay? Are you setting your life savings on fire?

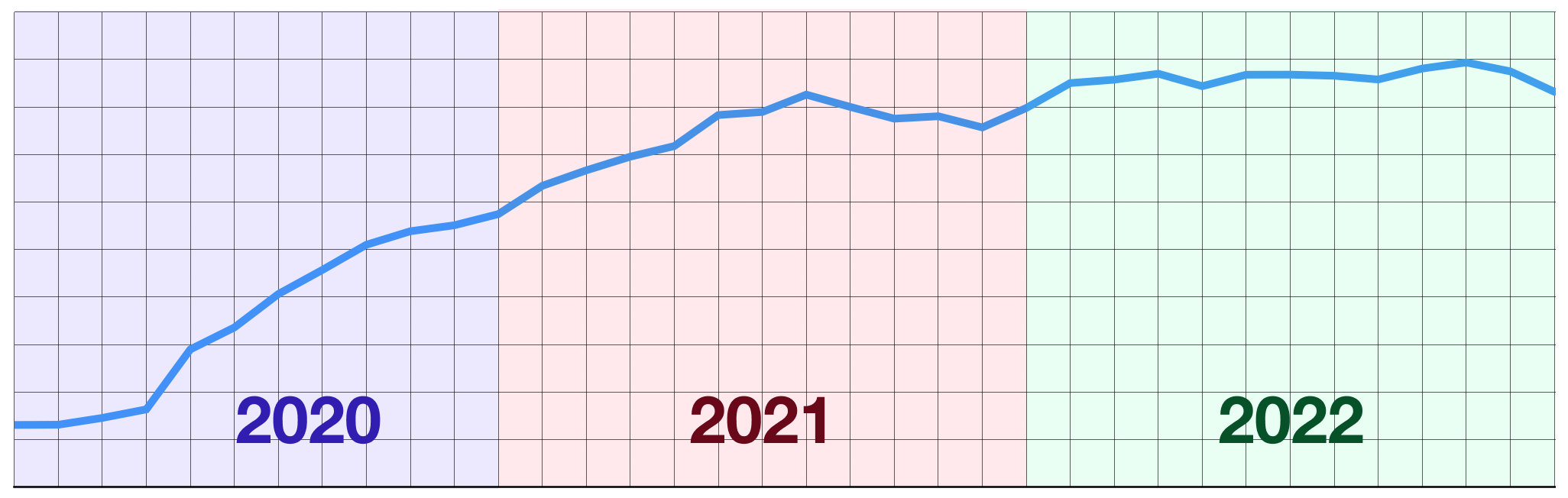

The good news is that I’m able to pay my bills. Really—strangers on the internet are able to pay my bills. (I’ll pause for a moment to say: this is unbelievable.) The bad news is that the program’s growth has roughly plateaued.

My income sits somewhere between that of a grad student and a junior faculty member. This is… okay, though obviously not ideal. And because early-career people often write me, eager to follow my path, I want to caveat: this only feels okay to me because I worked in tech for a decade and saved well; we own our home; my supportive wife has a stable career; we have no kids and no debt besides our mortgage; etc etc. In other words, because of phenomenally fortunate prior circumstances.

In my reflection on 2020, I quoted Ivan Sutherland:

I find that I have only so much room for taking risks. When I can reduce the risk in some places in my life, I can more easily face risk in other areas. I provide myself the courage to do some things by reducing my need for courage in other areas.

This is still very true for me! Unfortunately, I’ll confess that crowdfunding consumes a bit more courage now than it did two years ago. I’ve become somewhat less optimistic about its long-term sustainability. Flat revenue at my current level is okay, but the second derivative is probably slightly negative, and I’m not far into the black.

The fundamental dynamics haven’t changed since 2020: there’s a low but steady churn rate (~2% per month), which must therefore be balanced by a steady rate of new members. The churn rate is surprisingly insensitive to my actions. New perks, changing my publication rate, making (what seems to me) faster or slower progress—none of these things has meaningfully affected churn over the past few years. It’s sort of comforting to know this is probably not a knob I can meaningfully change.

New people visiting the membership page sign up at the same rate year over year, but there were fewer new visitors in 2022 than in 2021. As I pointed out last year, this means that to “tread water”, I need to constantly expand my audience, get new people “into the top of the funnel.” At least for me, this mode of thinking seems awfully toxic to a research mindset. If my crowdfunding revenue falls too much, I’d rather pursue grants and other funding sources than try to fix the situation through “growth marketing”.

It’s also pretty clear that a membership program like mine isn’t likely to fund a team or an institution. In previous years, I’ve experimented with hiring teammates on a contract basis, using a separate tranche of funds a few donors generously provided for that purpose. I continued those experiments this year, with quite a lot more success. And in 2023, I’ll be collaborating with a full-time research fellow for six months. I’m excited about these collaborations! To push further in these directions, I expect I’ll need some separate source of funding, not my membership revenue.

That all sounds a bit gloomy, so let me close this section by saying: crowdfunding does still successfully pay my bills. It’s not likely to stop in the next year. And that’s really astonishing!

Wonder and puzzlement

Let me focus on that astonishment for a moment. Day to day, I often lose sight of just how weird my life is. After three years of this arrangement, it’s somehow become… almost mundane? Homeostasis in all things, I suppose.

But at practically every social event I attend, I receive a reminder in the form of this conversation, which plays verbatim on loop:

“What do you do?”

“I’m trying to invent tools that give people unusual cognitive or creative powers.”

“Cool! Is that a startup?”

“Er, no, it’s just research. I make prototypes and write about them.”

“Oh, at a university?”

“No, I’m independent.”

“So you’re like a freelancer, hired for contract research?”

“No, I work on my own ideas.”

“But… who pays for that?”

“Uh… a bunch of people on the internet.”

All this usually leaves my counterparty expressing some mix of wonder and puzzlement. I have to say: that’s an awfully good description of how I feel about the situation, too, when I’m paying attention.

Wonder—here is the gift of an endless open field, to explore as I see fit. Craig Mod described this as “feeling bestowed a permission to do the kind of work I believed I was capable of, but perhaps not strong enough to do entirely on my own.” I get that too, and I’m grateful for it, but much of the wonder I feel arises from a sense of permissionlessness: I don’t need to seek anyone’s approval to pursue whatever I find interesting. With no grant applications to write and no tenure committee to appease, I can square up to the true task (the much harder task!) of courageously chasing what I actually think is best. Not what I imagine the crowd wants me to do; not what will likely produce shiny short-term results; not what will let me rest comfortably in my sphere of competence. It’s a towering call to action, and I’m tremendously grateful for it, and (of course) I absolutely struggle to live up to it.

And so, now, the puzzlement—what are the terms of this glorious freedom I’ve been granted? I’ve made few explicit promises to my members, sure. But they’ve likewise made few promises to me. What pace of legible progress must I maintain? How far can my interests stray? If enrollment starts to decline, will I be able to do anything to reverse that trend? At what cost? These are hard questions to ask on a survey. I don’t think I could answer them reliably myself, for other people I support through membership. I certainly don’t expect members to give me an unlimited leash.

What’s harder about this puzzlement is: even if I could answer those questions, I must not act on them! Say that I knew project X would take a long time, and my patrons would be likely to lose patience. So what? Would that mean I shouldn’t do it? That’s a recipe for a terrible research practice.

So, day to day, doing good research in the context of my membership program means mostly paying attention to the wonder, and to the gratitude, and mostly ignoring the puzzlement. That’s not easy!

What makes it easier is: practically every conversation I have with a patron is wildly supportive, trusting, and generous. These messages gently un-ask all those puzzled questions. Here are hundreds of people who are simply excited to see what I come up with. And when I manage to let go of my grasping puzzlement, all that faith redoubles my wonder.

So, to all members, past and present—thank you, thank you, thank you! These past few years have been the most creatively fulfilling of my life, and you’re part of a small group which has personally made that possible.

If you find my work interesting, you can become a member to help make more of it happen, and to get more essays like this one.

Finally, a special thanks to my sponsor-level patrons as of publication: Adam Marblestone, Adam Wiggins, Andrew Sutherland, Ben Springwater, Bert Muthalaly, Boris Verbitsky, Calvin French-Owen, Dan Romero, David Wilkinson, fnnch, Heptabase, James Hill-Khurana, James Lindenbaum, Jesse Andrews, Kevin Lynagh, Kinnu, Lambda AI Hardware, Ludwig Petersson, Maksim Stepanenko, Matt Knox, Mickey McManus, Mintter, Nathan Lippi, Patrick Collison, Peter Hartree, Ross Boucher, Russel Simmons, Salem Al-MansooriSana Labs, Thomas Honeyman, Todor Markov, Tooz Wu, William Clausen, William Laitinen, Yaniv Tal